Government Identification: BankID and the Australia Card

One of the less fun aspects of moving countries is that you become a walking edge-case for many IT systems. You’ll encounter online forms which don’t accept international phone numbers, government “change of address” forms which don’t accept international addresses, services which completely block access from international IPs, or systems which outright break if your address contains non-ASCII characters.

Being an expat also means becoming intimately familiar with all of the differences in provision of government services.

I’ve covered the Swedish BankID identity and authentication system in a previous post:

BankID is ubiquitous in Sweden, and for most of the services you’ll encounter as a resident, there is no username and password. You login to services using your personnummer, and you authenticate using Mobile BankID on your phone.

It works remarkably well—so well that many online services in Sweden have never had to worry about usernames and passwords, or the usual issues associated with them: storing passwords securely, password resets, and protection against credential stuffing. BankID handles this for them, and if they only cater to Swedish residents, that’s all they need.

And it can be used for much more than just logging in to websites. Because BankID uses a unique government-issued identifier (the personnummer), a service is able to identify users with enough confidence that they can use BankID for legally binding agreements. For example, you can obtain a loan from a Swedish bank using nothing but BankID.

One of the major disadvantages is this same reliance on the Swedish personnummer: if you’re not eligible for a number, or you haven’t received one yet, you simply can’t use BankID, and by extension, any service which uses it. For a foreigner living in Sweden, this is exactly as frustrating as it sounds.

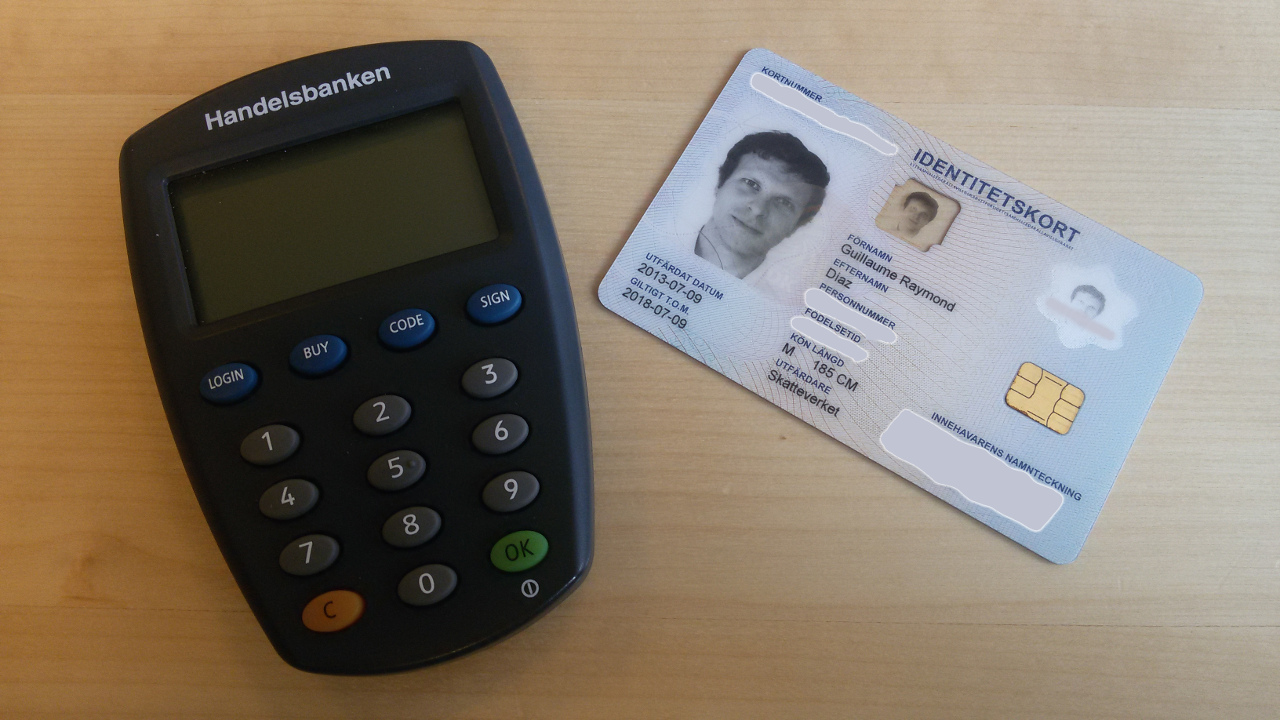

The system relies upon a physical BankID card issued by your bank. It’s a fairly standard smart card, containing a chip similar to the one in a modern credit card. The combination this card and a PIN allows you to prove—to a legally accepted degree of certainty—that you are who you say you are.

A card reader and Swedish ID card (technically not a BankID card, in this case).

A card reader and Swedish ID card (technically not a BankID card, in this case).

In modern usage, the primary job of this card is to set up Mobile BankID on a smartphone, which is significantly more convenient for most uses at the expense of being a slightly less trustworthy authentication method compared to connecting the BankID card and reader directly to a PC.

The benefit of all of this is that you can prove your identity to any Swedish government agency or business, no matter where in the world you currently happen to be, as long as you have your BankID card with you.

Australia: the 100 point check

Electronic ID systems like BankID are commonplace in northern Europe, and some jurisdictions use them for online voting in federal elections (notably Estonia). They’re much less common in the anglosphere.

In Australia, of course, there’s no such thing as BankID, and instead we use a “points” system for identification. Every time you want to open a bank account with a new financial institution, you’ll need to pass the 100 point check, which means providing a birth certificate, government-issued ID (like a passport or drivers licence), and other documentation.

The 100 point check is far from perfect, but given that Australia doesn’t have a strong central identity system like BankID, it works well enough. The problem comes when you need to authenticate yourself with the same service later. They verified your identity using the 100 point check, but how do they confirm this next time, such as when you need to be identified over the internet?

In practice, services use the same method as everyone else: username and password. This has the benefit of being ubiquitous and easy to implement, but has the significant downside of being only as secure as the passwords chosen by users.

Most people tend to use the same password everywhere, which means all of their accounts are at risk if a single one of them is compromised. This is bad enough for a Facebook or Google account, but it’s much worse when this includes access to an online banking system or a government service.

SMS as an identity mechanism

Australian banks and Government services are aware of the security problems which come from relying on usernames and passwords, so they often rely on codes sent via SMS as a secondary method of verifying a user’s identity.

The benefit of SMS is that it’s easy to use, and obtaining a mobile phone number in Australia requires some sort of identification to obtain in the first place (usually an address and a passport or drivers licence number). The problem is that SMS was never designed as a secure way to identify users, and it is quickly being deprecated in favour of more secure methods.

As an expat, one of the biggest problems with SMS is usability: users can become locked out of services entirely if they leave the country and no longer have the ability to receive SMS codes on their Australian phone number.

Indeed, the Australian Government’s official advice on the myGov website is to disable SMS two-factor authentication when leaving the country - reducing security in order to ensure users don’t lose access completely.

In 2018, this isn’t a tradeoff we should have to make.

The Australia Card and myGovID

The failed Australia Card was as close as Australians ever got to a national ID system like BankID. This proposal was incredibly controversial, as you can see in this 1988 article from the University of New South Wales Faculty of Law:

Readers of the Report will be familiar with the Australian Labor Government’s proposals for a national identification scheme, the pseudo-patriotically named ‘Australia Card’, and many of the arguments against it, from Roger Brown’s recent article. In my view, it would have gone beyond being a mere identification scheme, and would have established the most powerful location system in Australia, and a prototype data surveillance system totally out of keeping with the traditions of a common law country.

It is no exaggeration to say that the ID card proposal gave many Australians nightmares, and not only those of East European and Asian extraction. However, like all good nightmares, we woke one September morning to find that the nightmare was over.

The vehemence of the above excerpt might sound bizarre to those of you who live in the Nordics and take this sort of system for granted (there are significant cultural differences here which I won’t even try to tackle), but suffice to say that the idea of a central identification system caused a lot of pushback when it was proposed.

In any case, it seems that the Australia Card is making a comeback: the federal government recently announced a project to create a national digital identity system known as myGovID (also covered in a previous email).

It will be interesting to see what comes of the myGovID project, and whether it ends up looking like BankID and similar systems.