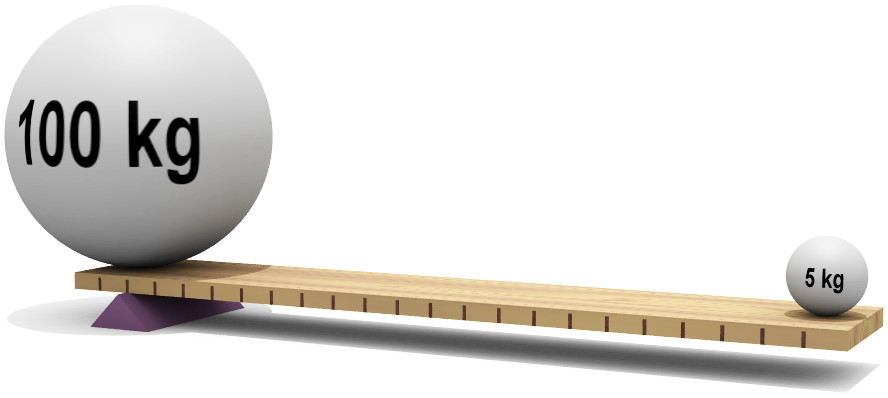

Security is always a trade-off

Trade-offs occur everywhere in engineering. Take leverage for example:

Leverage allows us to amplify a small force, by applying it at the end of a long lever. This is extremely useful, because it means we can move very large objects with much less effort than if we applied the force directly.

This might seem like a free win, but the trade-off is that we need more space to work in: more space for the lever, and more space to move it. If you have plenty of space, this isn’t a problem. If you’re working in a confined area, it might make using a lever impossible.

Engineering always involves compromises. The real skill is in knowing which ones to make, and when, in order to meet the design requirements of whatever you are building.

Convenience vs Security

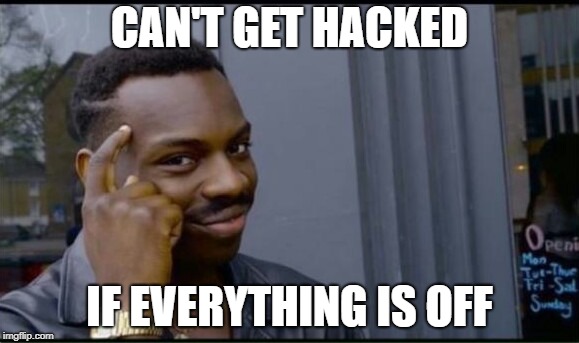

Everything we do in the security industry is a trade-off between convenience and security. Whenever we design a system, we are making a compromise between pure convenience (zero security) and pure security (zero convenience).

The latter is what I like to call the “turn everything off and go home” approach to security. After all, you can’t remotely hack a server if it’s always off, and no one can steal your corporate information if you never do any work!

Problem solved.

Problem solved.

This is an extreme example, but we’re all familiar with compromising convenience for security. Having to lock your computer is annoying, but we accept it as a necessary security precaution. Legitimate email gets caught in spam folders, but we still see the filtering as worthwhile.

There are also plenty of occasions where a system is designed so poorly that it ends up being both inconvenient to use and insecure. These are the low-hanging fruit in our industry (everyone likes a win-win), but focusing on these cases can make us complacent. Eventually we’ll run into a problem where we can’t have it both ways: we have to make a trade-off between convenience and security.

Even once we’ve made our decision, it gets more complicated. We might have selected the correct trade-off for our system, but our users might not agree—and making a security solution inconvenient for users tends to backfire.

Cormac Herley from Microsoft Research wrote a seminal paper on this topic back in 2009:

It is often suggested that users are hopelessly lazy and unmotivated on security questions. They chose weak passwords, ignore security warnings, and are oblivious to certificates errors. We argue that users’ rejection of the security advice they receive is entirely rational from an economic perspective. The advice offers to shield them from the direct costs of attacks, but burdens them with far greater indirect costs in the form of effort.

If it’s too much hassle to follow a security policy or to use a system correctly, people will work around it. This is especially true if they don’t appreciate the requirement or understand why it’s necessary.

They simply disagree with the trade-off you’ve made, and they’re correcting it for you.

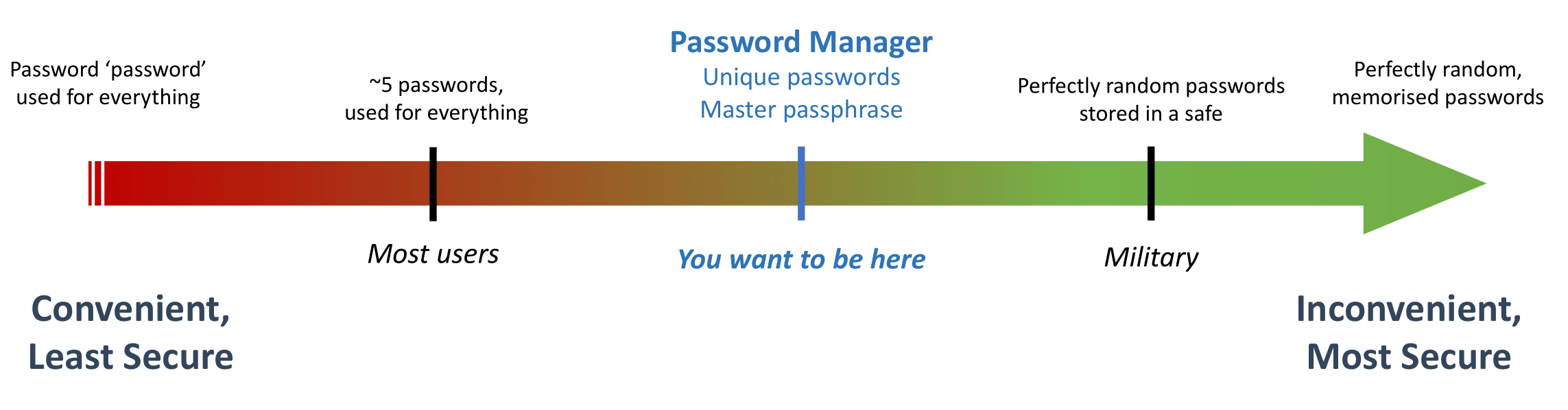

The security spectrum

We also have to compromise between security and convenience in our personal lives. For example, lets assume I’m trying to choose passwords for my online accounts. I have roughly 400 of these accounts: everything from Google and Facebook through to my local gym and tiny online merchants I only used once.

In this example, we can look at convenience and security as if they were a spectrum: one extreme representing maximum convenience (minimum security), and the other representing maximum security (minimum convenience).

Security is always a trade-off

Security is always a trade-off

The most convenient password is not to have one at all, but for these online services I’m forced to pick something. In that case, the easiest solution is to just use something ridiculously obvious for the password (like the word "password"), and use the same one for every service.

This is very convenient — I never need to remember a password again! — but is also incredibly insecure.

On the other end of the spectrum is the best possible password security: I’m going to randomly generate 200 character passwords in my head for every service I use. I won’t write them down (that would be less secure), so I have to memorise them all.

Clearly, this isn’t convenient or practical. There are a handful of people on the planet with a memory this good, but chances are you’re not one of them. Even if you were, this is ridiculous overkill for nearly any application.

Making the correct trade-off

When it comes to passwords, the majority of users are at the red end of our spectrum. People tend to have a small handful of passwords which they use for absolutely everything, and they’re usually not very good.

On the other end of the spectrum, if I want to make the “random passwords” method a bit more practical, I can write them in a physical notebook, and store them in a drawer at home. Contrary to popular belief, this is quite a good method for storing passwords. Anyone who wants to steal my notebook needs to physically break into my house, which significantly cuts down the number of attackers I need to worry about.

The problem with the physical notebook solution is that it’s inconvenient: every time I need to log into a service, I need to get my notebook out of the drawer, and I can’t copy-paste. If I need to log into something while I’m away from home, I need to bring the notebook with me. Very quickly, I’ll end up sliding down that spectrum by making compromises, because the solution was too much of a pain to use consistently.1

Again: overly inconvenient solutions tend to be self-correcting, to the detriment of security.

The correct trade-off for most people is to use a Password Manager. This strikes a good balance between convenience and security for everyday usage.

The concept of a password manager is very simple: you only need to remember one password, which then unlocks access to all of your other passwords. This means you can generate random and unique passwords for every service, and still have the convenience of having easy access to them.

This is still a compromise. Compared with the notebook method, trusting another service with my passwords reduces my security (especially if the notebook is stored in a safe when I’m not using it). Compared with using the same handful of passwords for everything, it’s less convenient (especially if I have to pay for the Password Manager).

Everything is a trade-off in engineering, but for this particular problem, it’s the correct trade-off to make.

Be honest about the trade-offs you are making

For most people, using a password manager is an easy compromise to make. Modern password managers are very convenient, so this solution comes close to being a win-win.

Security decisions become much more difficult when the convenience downside is obvious and painful for the user, but the change is nevertheless justified by the security improvement.2

When this happens, it’s important to be honest and transparent about the trade-off you are making. Users know that security improvements usually make their life more difficult. If they think you’re not being honest with them, or if you haven’t properly explained why the compromise is necessary, you’ll encounter much more resistance.

There’s always a trade-off. If we want people to sacrifice convenience for security, it’s important to be honest about the downside, and properly articulate why it’s worth it.

-

Remember that perception of ‘convenience’ will differ. For me, using a physical notebook for my passwords is incredibly inconvenient. For someone who isn’t confident with technology or doesn’t want to pay for a password manager, and who only logs into their accounts from their home desktop, it’s a different equation. ↩

-

Removing administrative privileges from users is a very common example of this, particularly for development teams and other technical employees. ↩