AMSI for Office macros, iPhone authenticated pointers, reinventing the URL, and infosec resilience

Good morning.

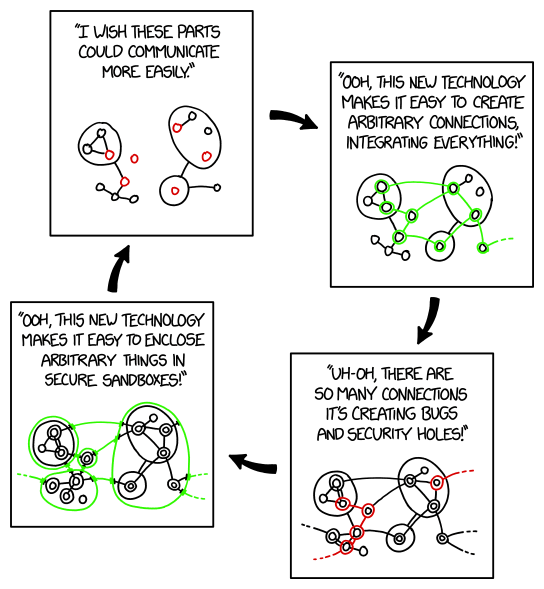

A recent XKCD comic made me chuckle:

“All I want is a secure system where it’s easy to do anything I want.

“All I want is a secure system where it’s easy to do anything I want.

Is that so much to ask?”

This is a theme I constantly return to: security is always a tradeoff.

Onto the news - we have quite a few stories to get through!

Microsoft extends AMSI to include Office macros

This is a very big deal. Microsoft has extended the Windows 10 “Antimalware Scan Interface” (AMSI) to include scripts executed by Microsoft Office programs, such as VBA macros.

From the Microsoft blog:

Macro-based threats have always been a prevalent entry point for malware, but we have observed a resurgence in recent years. Continuous improvements in platform and application security have led to the decline of software exploits, and attackers have found a viable alternative infection vector in social engineering attacks that abuse functionalities like VBA macros.

Office macros are incredibly useful when it comes to obtaining an initial foothold on a network, because they’re one of the only ways to guarantee reliable code execution.

Other techniques typically require a client-side exploit: corrupting the memory of a program like the user’s browser, Adobe Acrobat, or Microsoft Office. These are inherently unreliable (memory corruption exploits always run the risk of crashing the software they’re attacking), and tend to be patched quickly once they’re discovered.

In contrast, Office macros are a feature, and a critical one for many large organisations. Attacking a feature is always more reliable than exploiting a vulnerability, and Microsoft’s approach to backwards compatibility means that features tend to stick around.

The result is that in most corporate networks, using a macro as your delivery mechanism is the easiest and most reliable way to get code execution, and you won’t need to spend resources on discovering new exploits.

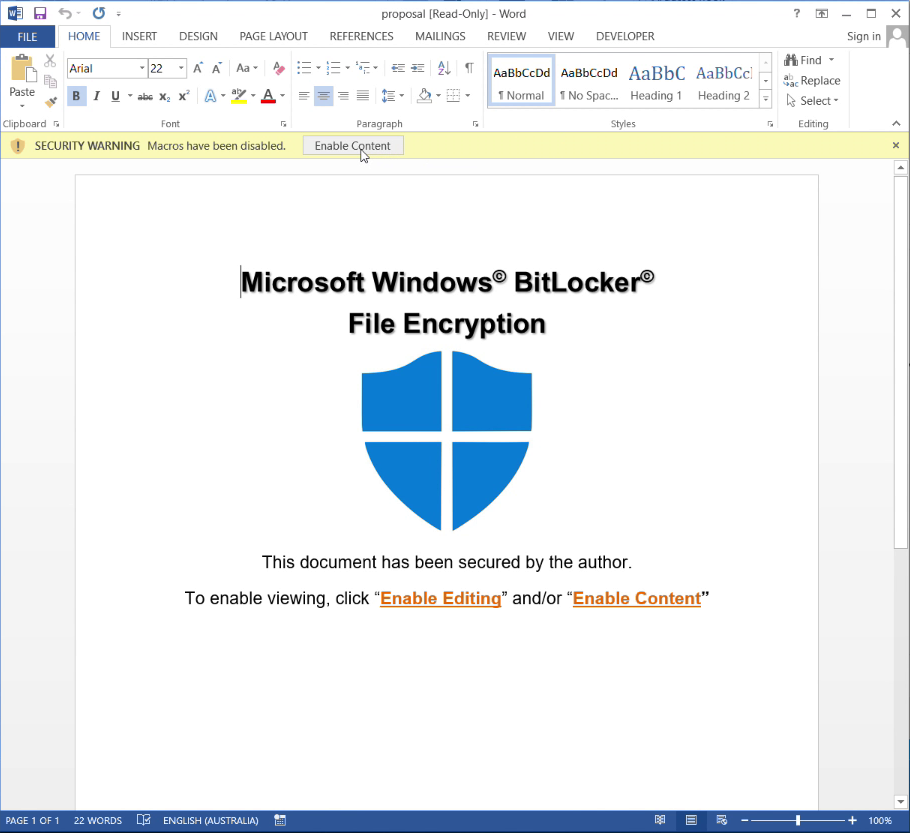

Of course, Office macros don’t automatically execute when opened, but it’s very easy to engineer users into enabling them for you.

For example, below is one I prepared earlier:

Go on, tell me you wouldn’t fall for that on a Monday morning.

Go on, tell me you wouldn’t fall for that on a Monday morning.

According to Cofense (formerly PhishMe), Office documents containing malicious macros accounted for 45% of malware delivery mechanisms in the month to 13 September.

Another popular techniques is to write the malware in JavaScript or VBScript and then name the file "invoice.pdf.js" or "invoice.pdf.vbs" - relying on the default Windows behaviour to “helpfully” strip the file extension and leave the file appearing as "invoice.pdf". When the user double-clicks the file, it’s executed as code just as if they’d opened "invoice.pdf.exe".

With Microsoft’s new update, AMSI now also integrates with the JavaScript and VBScript scripting engines, which also should make these attacks much easier to detect.

Props to Microsoft for this change - initial access just became a whole lot harder.

iOS Exploits and Authenticated Pointers

This story flew under the radar recently: the latest iPhones include the Apple A12 processor, which makes use of an incredibly neat feature called Pointer Authentication Codes (PACs). In short, this change is going to make it significantly harder to write working exploits for iOS.

If you’re interested, Patrick Gray recorded an excellent Risky Business feature interview last week which went into detail about the technology and it’s likely impact.

Reinventing the URL

The ABC recently did a feature on the Uniform Resource Locator we now take for granted, and the move by Google to rethink how URLs are displayed in Chrome.

The ABC did an excellent job explaining the security issues with URLs for a non-technical audience, and it’s worth a look.

If you have 30 minutes free, I’d also highly recommended this talk by Emily Schechter from the Chrome Security team. URLs are a classic case of bad usability making security difficult for end users, and Schechter’s talk covers all of the reasons why.

Resilience in InfoSec

Last on the list: this piece by Kelly Shortridge has been sitting in my “to read” list for a few weeks. I’m glad I didn’t skip it.

The Red Pill of Resilience in InfoSec:

You also must test your ability to absorb the impact of an attack, and minimize the damage. One such test is through failure injection. Chaos Monkey, part of Netflix’s suite of tools called the “Simian Army,” is a service which randomly kills instances in order to test their ability to withstand failure. In fact, Chaos Monkey is described as a resiliency tool.

While it was designed with a performance use case in mind, it can be repurposed for security. If your infrastructure is continually fluctuating, with instances killed at random, it makes it exceptionally difficult for attackers to persist. Attackers would have to conduct whatever they needed within an uncertain time frame. This is, of course, not impossible, but it absolutely raises the attacker’s cost and level of skill required.

Netflix’s goal with Chaos Monkey is to “design a cloud architecture where individual components can fail without affecting the availability of the entire system.”[22] Defenders should make it their goal to design a security architecture where individual controls can fail without affecting the security of the entire system. As I mentioned earlier, if your system becomes completely compromised because a user clicks on a malicious link, you must rethink your security architecture.

It’s an excellent piece, and worth reading in full.