Trustico and how not to manage SSL certificates

Good morning.

Today’s email is all about HTTPS, specifically the SSL certificates you use when you’re browsing secure websites, and the Certificate Authorities (CAs) who issue those certificates to begin with.

A certificate is how you know that you’re actually talking to Google’s servers when you browse to https://mail.google.com. The CA acts as a trusted third party, allowing your browser to independently confirm that it’s talking to Google, and not someone pretending to be Google.

Symantec and the Trustico Dumpster Fire

Lets start with where everything kicked off last week:

ArsTechnica: 23,000 HTTPS certificates axed after CEO emails private keys

A major dust-up on an Internet discussion forum is touching off troubling questions about the security of some browser-trusted HTTPS certificates when it revealed the CEO of a certificate reseller emailed a partner the sensitive private keys for 23,000 TLS certificates.

The email was sent on Tuesday by the CEO of Trustico, a UK-based reseller of TLS certificates issued by the browser-trusted certificate authorities Comodo and, until recently, Symantec. It was sent to Jeremy Rowley, an executive vice president at DigiCert, a certificate authority that acquired Symantec’s certificate issuance business after Symantec was caught flouting binding industry rules, prompting Google to distrust Symantec certificates in its Chrome browser. In communications earlier this month, Trustico notified DigiCert that 50,000 Symantec-issued certificates Trustico had resold should be mass revoked because of security concerns.

A quick aside about Symantec, because that’s an important story we haven’t covered previously:

- As mentioned above, a Certificate Authority (CA) is an essential part of secure websites: the CA is a trusted third party which signs certificates for other websites.

- Symantec owned several CAs, and was doing some very dodgy things with them.

- As a result of this dodginess, Google decided to start de-trusting Symantec-issued SSL certificates in Google Chrome, starting in April.

This is a big deal for any website which happens to currently be using a Symantec-issued SSL certificate, because anyone using Chrome will suddenly be presented with a big scary security warning rather than the website they were expecting.

Many organisations may not even be aware of this problem unless someone has pointed it out to them, or they read security news. For example, my superannuation fund Host Plus uses a certificate signed by a Symantec CA, and might end up having the rug pulled out from under them when Chrome stops trusting it.

Trustico: How (not) to run a CA

So how does this fit into Trustico? Well, Trustico is a certificate reseller, which until recently re-sold SSL certificates issued by Symantec. They now re-sell certificates from a different CA (Comodo).

The story is still very messy, but it sounds like Trustico has been trying to get their previous customers to replace their soon-to-be-useless Symantec certificates, by upgrading to new Comodo certificates. In order to force this, Trustico ended up sending the private keys for 23,000 TLS certificates over email, in order to have them revoked.

This is spectacularly stupid for all sorts of reasons, aside from the email stupidity. There’s no reason Trustico should have even had those private keys in the first place - the private key for an SSL cert should (ideally) never leave the server it’s being used on. A fundamental feature of the CA system is that a CA can sign your certificate without ever needing to see your private key.

From the Ars article again:

When Rowley asked for proof the certificates were compromised, the Trustico CEO emailed the private keys of 23,000 certificates, according to an account posted to a Mozilla security policy forum. The report produced a collective gasp among many security practitioners who said it demonstrated a shockingly cavalier treatment of the digital certificates that form one of the most basic foundations of website security.

Generally speaking, private keys for TLS certificates should never be archived by resellers, and, even in the rare cases where such storage is permissible, they should be tightly safeguarded. A CEO being able to attach the keys for 23,000 certificates to an email raises troubling concerns that those types of best practices weren’t followed. (There’s no indication the email was encrypted, either, although neither Trustico nor DigiCert provided that detail when responding to questions.) Other critics contend Trustico emailed the keys in an attempt to force customers with Symantec-issued certificates to move to Comodo-issued certificates. Although DigiCert took over Symantec’s certificate issuance business, it doesn’t count Trustico as a reseller.

Trustico tried to justify their action by stating they kept the private keys “for the purpose of revocation”. (To be clear, that’s entirely bullshit - you don’t need a private key in order to revoke an SSL cert.)

Trustico: How (not) to run a webserver

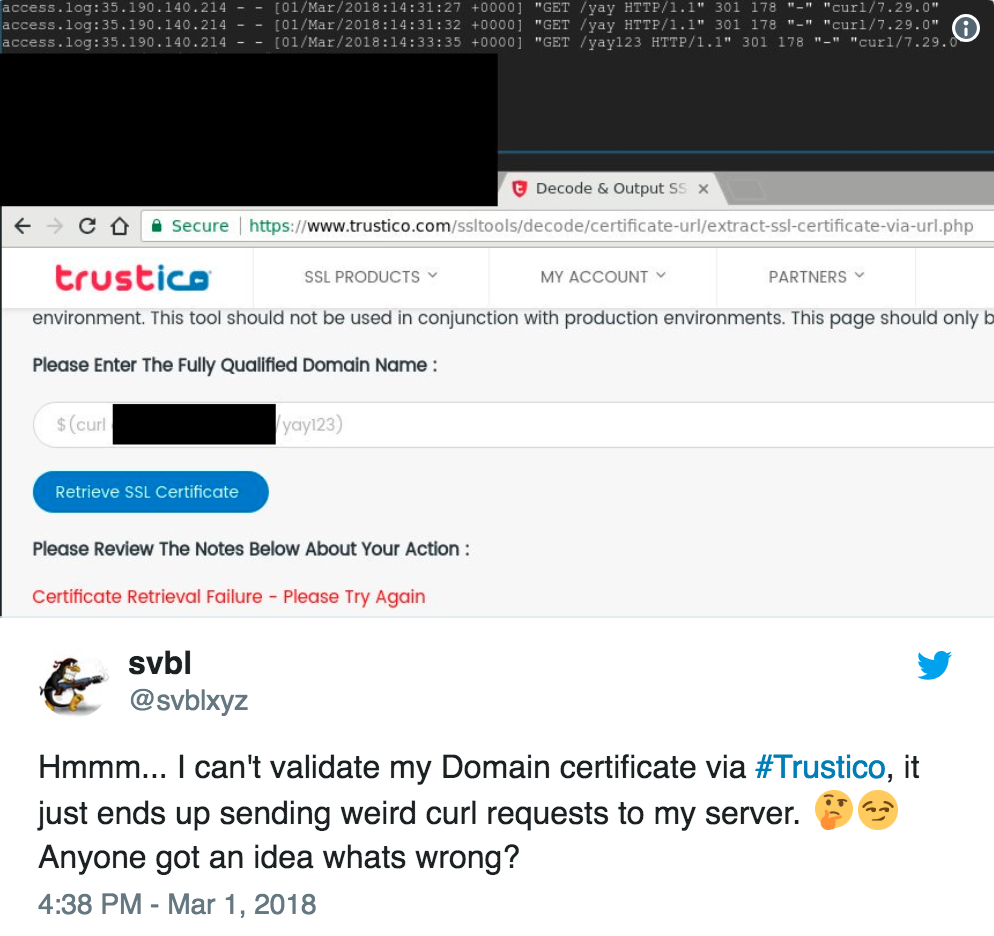

This is where the story gets really fun, because the next bit of news popped up on Twitter:

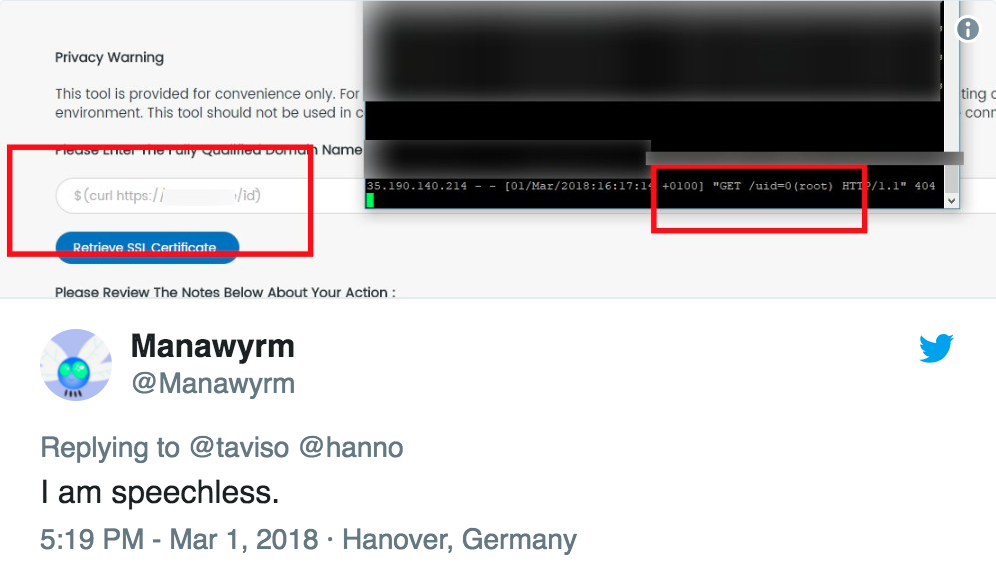

Followed by:

What’s happening in the first image is that there is a form on Trustico’s website which takes user input and doesn’t sanitise it properly, which means that you can run arbitrary commands on their webserver by just typing them in. (That’s bad.)

In the second image, someone realised that the commands were being run as root, so anyone who felt like it could nuke the entire server by just typing $(rm -rf /) into that form.

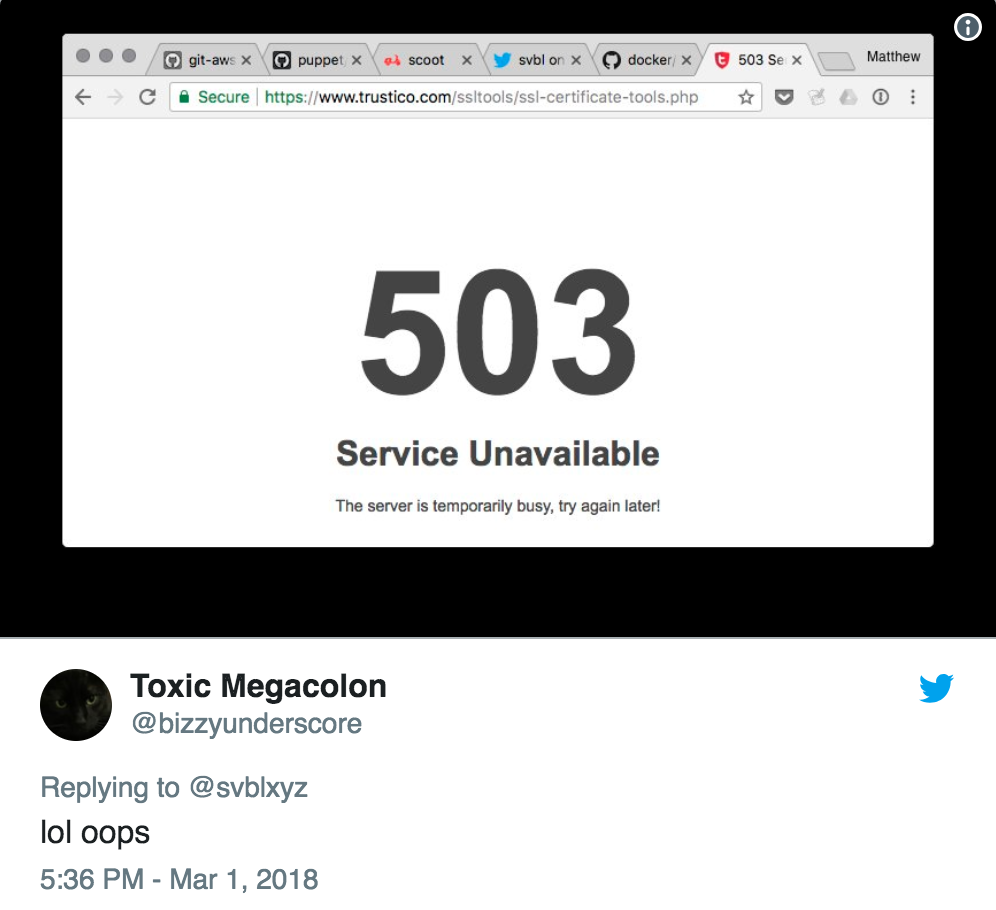

Sure enough:

I should be clear here: dropping a vulnerability like this over Twitter this is a real dick move, and a good example of irresponsible disclosure.

On the other hand, Trustico’s cavalier approach to security makes it hard to feel sorry for them, and companies this incompetent are often keen to threaten legal action against people who point out their shortcomings.

Eric Mill, an expert in public key infrastructure, said he was torn about whether posting the vulnerability to Twitter was justified.

“Just because you’re piling on a company that’s doing irresponsible stuff doesn’t make it OK to do a public disclosure,” he told Ars. At the same time, he noted, some Trustico officials have publicly claimed the mounting criticism against them is defamatory and have used other language to indicate they may take legal action against critics. Those types of behavior often have a chilling effect on more responsible forms of vulnerability disclosure. Ultimately, Mill said, “there are arguments on both sides.”

On both sides of the burning dumpster fire, yes.