HID attack demo and more supply chain attacks

So it turns out that free time is very hard to come by at a conference!

The good news is that I survived my trip to Austria for E-Vote-ID, the conference was excellent, and our paper was well received. The bad news is that my checked luggage is in a rail yard somewhere in Switzerland, due to my dumb self leaving it on a train.

Travel is hard.

Anyway, I’m safely back in Stockholm, and we enjoyed our first snow since arriving. Winter is coming.

HID Attacks

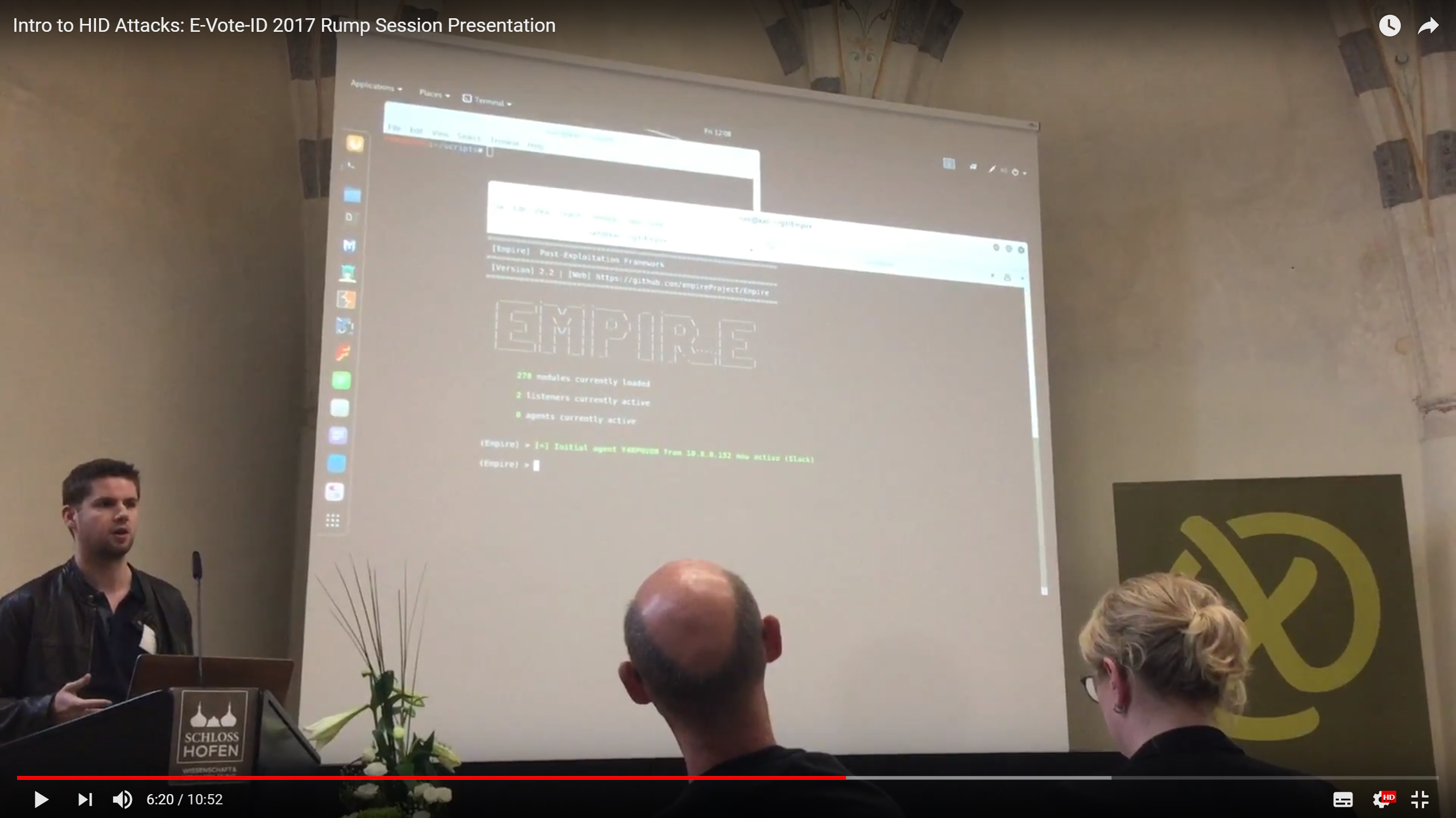

During the “Rump Session” at E-Vote-ID I presented a brief demo of a Human Interface Device (HID) attack, using my Bash Bunny. (Most of the people on this mailing list who have let me corner them for longer than 5 minutes have probably seen exactly the same demo.)

The video of the demo is here:

Intro to HID Attacks: E-Vote-ID 2017 Rump Session Presentation

The demo was filmed by Susan Greenhalgh of Verified Voting. Susan asked an excellent question at 4:12 regarding the possibility of this attack being used on air-gapped systems to re-enable any on-board wireless networking capability. Unfortunately I completely misunderstood her question at the time. Lesson learned: there’s a reason that good presenters re-state a question before they start answering it!

As I say in the conclusion of the video, there’s nothing novel about this attack: these techniques have been widely known and used by infosec people for many years.

The point of the demo was to show just how easy they are to perform with modern tools and frameworks, and to demonstrate them for an audience which also contained a lot of election officials and other people who aren’t spending their lives buried in infosec.

As I said during the presentation: being a script kiddie has never been easier.

Elmedia Player backdoored with Proton RAT

This story is old news at this point, but it’s worth mentioning because it’s part of a theme in the last few weeks of emails: supply-chain attacks.

Hackers Distribute Malware-Infected Media Player to Hundreds of Mac Users

Security researchers from antivirus firm ESET reported Friday that the free version of Elmedia Player distributed from Eltima Software’s website contained a macOS information stealing trojan known as OSX/Proton. The same malware was distributed earlier this year through another trojanized version of a popular macOS application called HandBrake.

Eltima told me in an email that hackers also managed to trojanize one of the company’s other applications, an internet download manager called Folx that also acts as a BitTorrent client.

The Proton malware is capable of stealing a lot of data from infected computers including history, cookies, bookmarks, and log-in data from browsers; cryptocurrency wallets; SSH authentication keys; macOS keychain data; Tunnelblick VPN configuration data; PGP encryption keys and data stored in 1Password, a password management application.

Proton obtains root privileges when it’s installed (because it’s piggybacking on another installer, and requests your root password during the install process), so that last paragraph is a long-winded way of saying “it can do whatever it wants”.

Proton is a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) designed specifically for OSX/macOS. It’s professionally made, and is sold to criminals wanting to use it to steal bank credentials or do other very black-hatty things.

It even comes with its own very slick web interface, which is kindly demonstrated by the developer here.

The general consensus for cleaning a Mac infected with Proton is “wipe and rebuild”, which is just shy of “nuke it from orbit”. Once something this good has root, it’s a massive pain to dislodge it, and you’re usually just better off burning your system to the ground and starting from scratch.

The real question is how this happened, given that it’s the latest in a string of infections using application updates as an attack vector. From the article:

The attackers don’t appear to have compromised the company’s development infrastructure, as happened recently with the developer of a Windows application called CCleaner. Instead, the hackers just managed to hack into Eltima’s website through a vulnerability in a JavaScript-based library called TinyMCE.

The malicious installers were not digitally signed with Eltima’s Apple developer certificate, but with a different developer ID under the name Clifton Grimm. It’s not clear if this certificate was obtained from Apple by using a fake identity or if it was stolen from another developer.

Gatekeeper, Apple’s first line of defense against malware, allows signed binaries to execute without warning by default, Patrick Wardle, director of research at Synack and a macOS security expert, told me in a Twitter direct message. Because of this, most Mac malware is now signed with stolen or fraudulently obtained Apple developer IDs, with the latter being much more likely, he said.

“It appears Apple has a problem with ensuring only legitimate developer IDs are given out,” Wardle said.

Apple revoked the misused Clifton Grimm certificate after being alerted by ESET and Eltima, but users who downloaded and executed the rogue Elmedia Player and Folx installers before this happened didn’t get a Gatekeeper warning.

So this wasn’t as sophisticated as the CCleaner attack from last month, where the attackers owned a development system and backdoored the software before it was signed by the developer’s certificate.

Instead, in this case the attacker just owned Eltima’s website and replaced the original installer file with a new one, signed by a completely different Apple Developer ID. Anyone who was already using the software wasn’t affected (they didn’t infect the auto-update), just those people who happened to download the software before the attack was discovered.

If you ask what sort of attacks worry me (in a personal security sense), it’s these ones. Forget fancy 0-days or state actors breaking into my apartment to swap out hardware - this is the sort of attack which is most likely to hit techies, and there’s not a lot you can do to mitigate it.

If you use any software which auto-updates, and someone owns that update mechanism, you’re screwed. Even if you refuse auto-updates, at some point you’ll need to update, or risk the software itself being insecure. Even this doesn’t buy you a lot more assurance - no one is going to reverse-engineer all of their updates and check for backdoors.

Your only mitigation is to hope that the developer has good security practices, and that’s not a fun position to be in. As always, only install software from well-known developers that you trust, and consider whether or not you need to auto-update absolutely everything.

I unfortunately don’t have any better solutions for this problem, but it’s something the OS vendors need to take more seriously. Apple’s Gatekeeper (mentioned in the article) is excellent, but there’s scope to add additional restrictions on what software can be executed under what developer certificate, to prevent someone using fake/stolen certs to sign backdoored versions of another developer’s software.

Unfortunately, as with all aspects of security, more assurance means more hassle. “Risk equals return” holds true for more than just investments.