Efail and Chrome HTTPS indicators

Good morning.

It was a big week in security, but before we get stuck into the news, another book recommendation (I’ve been on a roll with my reading lately): The Big Four: The Curious Past and Perilous Future of the Global Accounting Monopoly.

For those of you who currently work for a Big Four firm, don’t be too alarmed by the blurb. It’s an extremely interesting book, and it describes the history of the Medici Bank and its importance in creating the franchise and partnership model used by the Big Four today.

The Medici Bank was also a major influence on the double-entry bookkeeping system we now take for granted, along with many other accounting controls which are severely underappreciated.

Efail and email encryption

The biggest story of the week was the so-called ‘efail’ vulnerability, disclosed in the typical fashion using a branded website.

If you have 5 minutes and a pair of headphones, the best summary you’ll get will be this one from Adam Boileau, on the Risky Business podcast. He also goes into some detail about making bad security trade-offs (a pet topic of mine!), namely: people choosing to use rich-client email or messaging applications on their desktops in order to gain better privacy against network sniffing attacks, but in the meantime opening themselves up to direct exploitation through remote code execution bugs.

Another excellent response to the ‘Efail’ story was written by Matthew Green, a very well-regarded cryptographer from John Hopkins University (he also features as the lower-left section of the Risky Business “quartered rhombus of cyber ownage”):

On Monday a team of researchers from Münster, RUB and NXP disclosed serious cryptographic vulnerabilities in a number of encrypted email clients. The flaws, which go by the cute vulnerability name of “Efail”, potentially allow an attacker to decrypt S/MIME or PGP-encrypted email with only minimal user interaction.

By the standards of cryptographic vulnerabilities, this is about as bad as things get. In short: if an attacker can intercept and alter an encrypted email — say, by sending you a new (altered) copy, or modifying a copy stored on your mail server — they can cause many GUI-based email clients to send the full plaintext of the email to an attacker controlled-server. Even worse, most of the basic problems that cause this flaw have been known for years, and yet remain in clients.

The rest of the post is focussed on the backlash to the way the vulnerability was disclosed, particularly from portions of the PGP community:

Now that I’ve made it clear that neither the researchers nor the EFF is out to get the PGP community, let me put on my mask and horns and tell you why someone should be. […]

The fact of the matter is that OpenPGP is not really a cryptography project. That is, it’s not held together by cryptography. It’s held together by backwards-compatibility and (increasingly) a kind of an obsession with the idea of PGP as an end in and of itself, rather than as a means to actually make end-users more secure.

Chrome removing Secure indicator for HTTPS connections

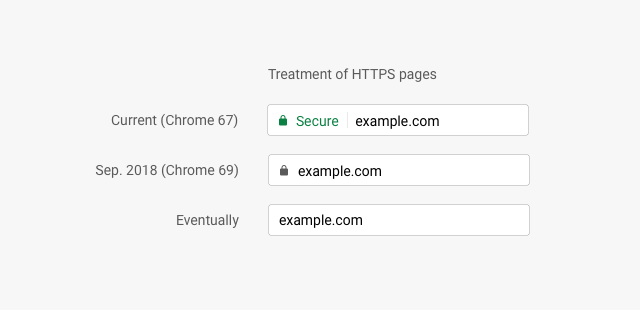

This one is a big deal: Chrome will be removing the ‘Secure’ indicator for HTTPS websites as of September. This is a major shift: instead of highlighting encrypted connections as ‘secure’, Chrome will instead highlight unencrypted ones.

The background to this change is the Web’s gradual migration to the use of HTTPS rather than HTTP. With an ever-growing fraction of the Web being served over secure HTTPS—something now easy to do at zero cost thanks to the Let’s Encrypt initiative—Google is anticipating a world where HTTPS is the default. In this world, only the occasional unsafe site should have its URL highlighted, not the boring and humdrum secure site.

The result will look like this following:

In a remarkably prescient post, Troy Hunt wrote about exactly this issue on the 7th of May:

On those changes, there will likely be a time where the positive visual indicator that is the padlock can be removed entirely. Think about it - when (almost) every site is HTTPS anyway, why have it? You could instead fall back to ever more negative visual indicators when sites aren’t served over HTTPS and we’re only a couple of months out from seeing the beginning of that. Wouldn’t it be great if we could kill the padlock and the indication of the HTTPS scheme off altogether and just flag the exceptions? We’re getting there.

He’s spot-on, and the full post is worth reading in full. It perfectly articulates many of the issues with our current approaches to ‘Secure’ websites and how we get users to trust them.

Other reading

Another couple of excellent articles which are worth saving for your next flight:

- 10 things infosec professionals need to know about networking

- Quora: What is the most sophisticated piece of software code ever written?

The first is a topic near-and-dear to my heart. I’m extremely appreciative of the six years I spent writing satellite communications waveforms, because it forced me to learn more about low-level networking than the average Computer Science graduate ever encounters either during their studies or once they start working in industry. Understanding how things work under the hood is essential in security, and very useful everywhere else.

The second link is a fantastic Quora answer about the Stuxnet malware. Most of you would be familiar with the story behind Stuxnet, but even if you are, it’s one of the better summaries I’ve seen.