Cisco and Cryptomining

There’s a lot to get through in today’s email, but first of all I wanted to make another mention of the SpaceX Falcon Heavy Launch, which went off extremely well last Tuesday.

I was honestly expecting the thing to break apart and explode either shortly after lift-off or when it hit Max-Q (maximum dynamic pressure), but the rocket worked beautifully. The simultaneous side-booster landing was one of the most impressive things I’ve ever seen.

I know I’m fanboying a bit with this SpaceX stuff, but I can’t help it. Landing and re-using a booster like this was considered to be impossible only a couple of years ago. It’s a game-changer for commercial spaceflight, and SpaceX now has the most powerful rocket in the word by a factor of two - for half the price-per-launch of its nearest competitor.

There’s a very good argument that if we don’t become an interplanetary species in the next generation or two, we never will - so this is kind of a big deal.

Cisco’s Clusterf**k

I’m not mincing words with this one because it’s been a royal pain in my arse for the last week.

A massive vulnerability was recently made public for Cisco’s ASA firewalls, particularly when they’re running as VPN endpoints. The vulnerability was classed as a 10 on the CVE scoring system, which is the highest that it goes.

That mega-vulnerability Cisco dropped is now under exploit

The vulnerability’s maximum severity rating results from the relative ease in exploiting it, combined with the extraordinary control if gives successful attackers. Devices running Cisco ASA software typically sit at the edge of a protected network, making them easy for outsiders to locate. Once exploited, the devices allow remote hackers to seize administrative control of networks and to monitor all traffic that passes through them.

Lets be clear here: for many organisations, this vulnerability will be a far bigger problem than Meltdown and Spectre were.

Someone exploiting your Firewall or VPN endpoint is as bad as it gets - these devices are exposed to the internet by design, they usually have access to all of the internal networks, and they’re often configured so that users authenticate using Active Directory domain credentials.

In short: if you pop a Cisco ASA running as a VPN endpoint, you’re going to have a very easy time making a mess of the rest of the corporate network.

To make matters worse, Cisco’s original advisory was revised a few days later once they discovered that it was worse than they originally though (again, they originally thought it was a severity of 10), and they re-issued the patch, which meant that a lot of organisations had to go through the process of patching twice.

This is the third time that this has happened this year: first was the VMware critical vulnerabilities which were pulled and re-issued, then the mess with Intel’s Meltdown and Spectre patches. Now we have Cisco.

One of the biggest problems with the haphazard nature of these patch releases is that it’s causing companies to think “don’t bother patching this critical vulnerability yet - there will be a new patch in a week anyway.”

That’s the worst possible lesson to learn from these messes, but you can’t blame them for it.

Supply chain attack introduces cryptomining malware to websites everywhere

This one was bound to happen sooner or later.

In a previous email I mentioned the excellent Hackernoon post by David Gilbertson, where he described a hypothetical piece of malicious Javascript introduced as an NPM package and surreptitiously included in websites all over the internet to harvest credit card details.

Well, apparently someone took the lesson to heart, and decided to do the same thing with a JavaScript cryptocurrency miner:

Australian govt sites hijacked by crypto miner

More than 4000 Australian and global government websites have been hijacked to run the Coinhive crypto currency mining software after a popular accessibility tool was compromised by attackers.

Security researcher Scott Helme today published his discovery of 4275 government websites across the globe that have been hijacked by Coinhive. The list spans the US and UK as well as Australia. Both federal and state government websites locally are included in the list.

The Queensland government’s main site for its legislation has been hijacked, as have websites belonging to the likes of Queensland Urban Utilities, the Victorian parliament, and South Australia’s City of Unley.

The problem stems from a website plug-in called Browsealoud that helps blind and partially sighted people access the web. The plug-in was tampered with overnight to add the Coinhive program. Coinhive mines for the Monero crypto currency.

“If you want to load a crypto miner on 1000+ websites you don’t attack 1000+ websites, you attack the 1 website that they all load content from,” Helme said.

Yep.

Nice work to whoever did it. Fortunately, there was no permanent harm done to anyone who visited the compromised websites. As I mentioned in the last email, this sort of cryptomining attack is probably the best outcome you can hope for if someone manages to execute code on your computer.

The CoinHive mining software has been popping up everywhere of late, because it makes it extremely easy to mine Monero on someone else’s computer with just a few lines of Javascript. With a single victim that’s hardly worth the effort, but—as with denial of service attacks—if you can collect thousands of victims, it adds up.

Supply chain attacks, fragile security, and fear of updates

We’ve covered supply-chain attacks several times in these emails, but they’re really starting to ramp up in frequency.

The problem with this style of attack is that it’s a complete blind spot for most organisations—even those who get audited regularly. Even the most thoroughly scoped penetration test in the world will never cover supply-chain attacks, because there’s no way you’ll get legal permission to hack a third-party just to obtain access to your client’s system.

Due to this blind spot, even organisations with good security practices likely have little concept of what a well-executed supply-chain attack can do to their infrastructure.

We’ve talked about backdooring tools like Putty and Plink in previous emails, but it doesn’t stop there: think of how many system administrators use Notepad++ or other popular free tools, and what you could do if you managed to introduce a malicious update (which installs with full Administrator privileges). Bonus points if they’re using it on a Domain Controller.

Good operational security is really hard, and people who are busy trying to get work done rarely make the time to do it right.

It’s only a matter of time until we have another major attack on the scale of NotPetya, delivered via a compromised auto-update or similar. As with the messy VMware/Intel/Cisco patch releases, the largest long-term consequence is that it’ll destroy the message we’ve spent decades telling users: “patch your stuff”.

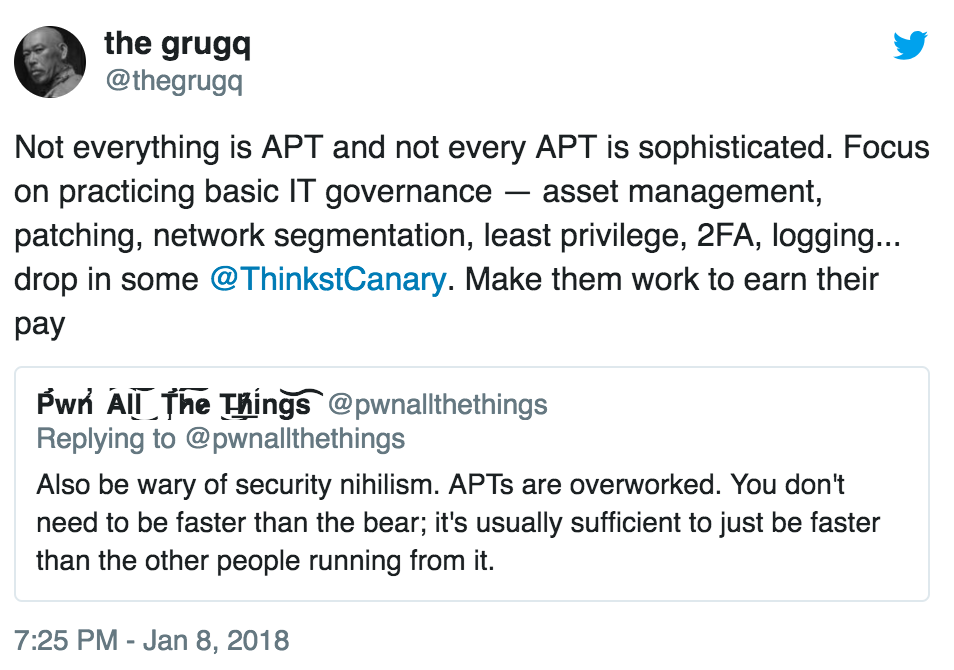

As always, it’s easy to throw your hands in the air, but remember: the bad guys aren’t perfect. The best defence is to get the basic hygiene right: