Certstream, Let's Encrypt, and phishing with TLS certificates

Today’s email is all about TLS certificates:

CertStream is an intelligence feed that gives you real-time updates from the Certificate Transparency Log network, allowing you to use it as a building block to make tools that react to new certificates being issued in real time. We do all the hard work of watching, aggregating, and parsing the transparency logs, and give you super simple libraries that enable you to do awesome things with minimal effort.

This is pretty neat. You might notice that 99% of the issued tickets in the feed are from Let’s Encrypt, which isn’t surprising: Let’s Encrypt is free, and you have to renew your certificate regularly: both of these add up to a large number of certificates being issued constantly.

Let’s Encrypt has done more than anyone else for increasing the use of HTTPS on the internet, but unfortunately this has also come at a cost.

Free TLS certs = way more effective phishing

It’s always been possible to register a phishing domain, such as www.google.com-------fadf--fdg-dodgy.mcdodgyson.com, and get yourself a domain which looks like Google if you only see the first part of it.

However, it’s now also trivial to get a trusted TLS certificate for your phishing domain, which is a real game-changer for phishing campaigns.

Consider the below image, which is what you see if you visit a site with what’s called a Domain Validated certificate, or “DV cert”.

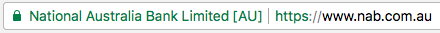

Compare with the next one, which is what you see if you visit a site with an Extended Validation certificate, or “EV cert”.

Both screenshots are from Chrome, and you’ll notice that there isn’t a dramatic visual difference between the two, especially if you’re not looking for it.

There is a major difference in how you obtain the two types of cert, however:

- A DV cert simply requires you to prove that you control the domain in question.

- An EV cert can only be purchased from certain Certificate Authorities (CAs), requires you to prove that you control the domain in question, and also requires identification that you’re a legitimate business, in addition to a bunch of other stuff designed to increase the level of confidence that you are who you say you are, on top of spending a lot of money.

Unfortunately, at various times in previous years the providers selling EV certs have resembled a protection racket, and the expense of obtaining a certificate was one of the reasons that many business considered SSL/TLS too much hassle to deal with.

It’s also important to note that the major tech companies such as Google and Facebook only use DV certs these days - so they clearly don’t see any great advantage in using EV certs.

And there isn’t really, in practice… except that with Let’s Encrypt giving them away DV certs for free, it’s now way more practical to create a few dozen phishing domains, all with their own TLS certificate.

Usability and phishing

Most users will see that green ‘lock’ icon in their address bar and assume that this means two things:

- Their connection is encrypted (or at least “secure”), and

- The person on the other end is who they claim to be

The problem with TLS certificates is that you only really have assurance of point 1 above. There’s no guarantee that the server on the other end of the connection is actually who you think it is, because “who you think it is” is based on a lot more context than just the domain or URL.

Remember: if you click on the link to dodgy.mcdodgyson’s phishing domain, the URL bar will still have the nice shiny green lock, and you might completely miss the fact that the URL itself looks off:

With this domain and some clever wording in my phishing emails, I’ll probably have quite a bit of success capturing credentials by sending people that link. Especially if the organisation I’m phishing happens to use something like Office 365 or Google Docs.

Enter Certstream, which has some cool use cases: you can slurp down this stream of registered certificates, search for your organisation’s name (such as google, above), and spot if someone is registering certificates and domains to use for phishing. It’s a nice way to get some forewarning that your name is being used for phishing campaigns.